4. The Calabozos of la Princesa

Jesus Santiago is dropped off at a colonial prison in old San Juan. The warden suspects him of having a connection to the FBI's wooden crate. He has no idea it goes back to 1518... and John Spillers.

Previously—In part 3, The Memories of Trees & Men, we peeked into the interrogation facility at Ramey Air Force Base, and learned about two of its occupants: a 460 year old ceiba tree and Captain Cristian Monserrate Sepulveda.

In this post—we're introduced to Jesus Santiago, an old jibaro who is dropped off at la Princesa prison. Right away, he meets the warden, who suspects the old man of having some connection to the wooden crate recovered by the FBI, now in the hands of John Spillers. Santiago, it turns out, has history with the man with yellow hair... Spillers.

Thursday, 5 October, 1950

On an unusually humid morning, two prison guards unlocked and opened the wrought iron door leading out to the promenade along paseo de la Princesa. Up ahead, twenty or so feet, two cops sit in a freshly waxed cruiser, each with an arm dangling out the window. A shoeless silver haired man sits in the back. His name is Jesus Santiago, and he was arrested three hours earlier by the men in the front seat. When the prison guards sidle up to the car to chit chat with the cops, right away they assume the old man is the jibaro from the mountains—the one the warden mentioned. He looks to be sixty years old—straight off a poster promoting Operation Bootstrap. He’s wearing a long sleeve white collared shirt over a white under shirt, heavy duty brown work pants, and his skin, the color of tawny port has deep furrowed wrinkles like the thin grooves on the surface of an almond. Unlike the jibaros from the posters, there’s a shine in his eyes.

“Vamos viejito” one of them said, opening the back door. Just as they both had predicted, the old man wasn’t wearing shoes. When he stepped out of the cruiser, and planted his bare feet on to hot cobblestone, he did so with a playful smile and balletic springiness that surprised them both a bit. Anibal, the taller of the two, assumed the old man was simple, and kicked at his heels from behind for most of the walk into the prison. The other one, Miguel, chuckled from time to time, smoking a cigarette and once in a while jabbing his baton into the old man’s back. This is how Jesus Santiago was escorted into la Princesa prison to meet the warden.

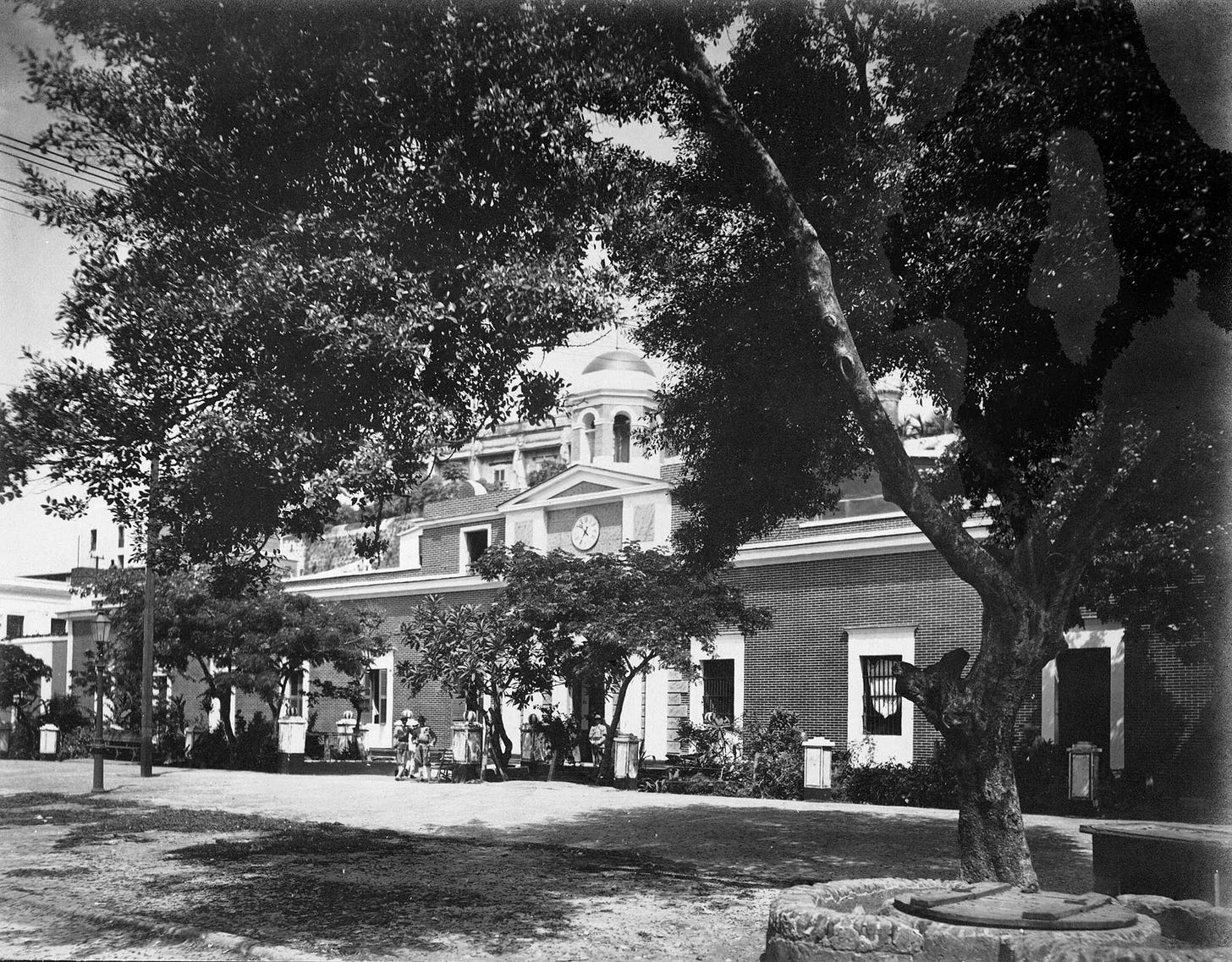

They walked through an iron gate below a clock, into a foyer with a polished marble floor, toward a pair of tall doors leading into a courtyard, past a fountain, down a narrow passageway, then through a doorway that has no door. At the end of this stone hedge maze, they arrive at a large open-air pocket chamber with no roof—just three partition walls of brick and stucco. The fourth wall is a stone colossus—part of the three mile long forty two foot high defensive rampart protecting old San Juan. In front of that wall stands a fat stump of a man dressed in a grey linen double-breasted suit, coughing into a handkerchief. “Just tell me what’s in the crate.” he says, balling up the handkerchief and dabbing his forehead with it. He’s Pedro Alvarez, warden of la Princesa prison—a five foot seven, two hundred and forty pound Christmas tree shaped man. Santiago can smell his breath before he completes his sentence. He says nothing for a long while, but beams at the warden with his playful smile. The warden rolls his eyes, moves a step forward, and brings his hands up, as though holding an invisible crate-sized object, and says, “The crate they found on your land. What’s in it? Why do you have it? Tell me that and you can go.” Each time the warden opens his mouth, the guards angle their faces, the same way a plumber would, when unsealing a toilet flange. Santiago’s eyes go down to the warden’s belt buckle. He imagines just below the subcutaneous carpets of skin and fat, a gelatinous casserole of bloody fibroids and half-digested meat, swirling in a brine of rectal discharge.

“What crate?” Santiago says, shrugging. He hears a snicker from behind, and feels the tip of a wooden baton pressing into his back.

The warden drops his hands, shakes his head and frowns. Anibal sees this, brings his baton up, and whacks hard at Santiago’s calves. The old man sways a bit, laughs, and says thank you. He calls the men his puchungitos—his little cuties. The warden is silent for several seconds, unprepared to process this reaction. His eyebrows are climbing up his forehead. Finally, he shuffles forward and slaps Santiago’s face, nearly tripping in the process. When he regains his footing, he wipes his fingers off on his coughing handkerchief, panting and wheezing through an open mouth. There are beads of perspiration forming on his forehead and upper lip. The guards are horrified, which seems to confirm that the warden is in fact belching out millions of tiny casserole molecules, bursting and befouling the air.

“Find out what’s in that fucking crate.” he says to the guards. “I’m going to wash my hands and take a shit.” He tosses his handkerchief on the ground and disappears out of the doorway that has no door, and back out into the stone hedge maze. The guards look relieved.

When the warden returns, he’s in a better mood, and with two fresh handkerchiefs in his pocket. He steps into the doorway puffing on a cigar, but stops cold as soon as he sees how the interrogation has gone. It’s been twenty minutes. Both guards are bent over, slicked with sweat. Their hats are off—lying on the ground in a corner next to their folded up shirts. Their trousers have long dark stains of perspiration around the front pockets, where they’ve been wiping their hands. Santiago is standing up tall and straight, looking cheerful and saying gracias mis puchungitos—over and over.

“Put him in a calabozo.” the warden says. “See how he likes it in there for a few days.” And then he disappears around the corner, wet coughing the whole way down the narrow stone passageway, leaving a wake of toilet casserole fumes behind him.

The guards put their shirts back on without speaking, one button at a time, not bothering to tuck them in. With hats hanging off their heads at a tilt, they slow-walk Santiago out the same doorway they came in, then along the narrow passage. They pass through the main courtyard where a dozen or so prisoners are milling around—shattered ruins of men arranged like exploded cargo. There are three prisoners with elephantiasis seated at a table, playing dominoes. They look to be the fittest. A few hunchbacks and paraplegics amble slowly around the table with brown bandages drooping off their faces. Another man is sitting down on a stone with a wet towel wrapped around his head—pants torn open to reveal shins so swollen, they look like twin spools of lamb meat on a rotisserie. His skin is pock marked with large moist looking pores, like nearly set cake. There’s a thick stream of yellow discharge running down one of his legs which the man gingerly pats with his palms, then wipes along the wet towel.

Ten feet away, two emaciated prisoners who could be twins, are laying down in a patch of shade, arranged head to head, perhaps some kind of strange napping ritual. They’re both barely moving. Their faces and necks are stained dark brown, almost purple, as if they dunked themselves in buckets of grape juice. Santiago understands instantly what he’s looking at. It’s an old campesino trick to keep mosquitoes away: chewing up tobacco leaves and smearing the nicotined saliva on your skin. He wonders where they got the tobacco from.

Ahead, where the guards are leading him, he hears a small distant voice ensconced in stone, counting… ‘947, 948—’. An hour from now, Santiago will learn that this man is known as el contador (the counter)—a twenty five year old graduate student from Jayuya, serving a five year sentence for carrying a wallet-sized photo of a Puerto Rican flag inside of a math book—in violation of la ley de la mordaza—better known as the Gag Law. Instead of getting his phd in economics, el contador recites numbers all day long.

There are several other prisoners strewn around the courtyard—all making only the tiniest of movements—like human-sized mechanical implements in various states of failure. Perhaps, in an effort to conserve their dwindling energy stores, they command themselves to move at the slowest possible rate; in a kind of metabolically reduced tapering disintegration.

Once past the men in the courtyard, Santiago is led towards another passageway. As they enter, he immediately walks into a curtain of stench. Directly in front of him, there are two rows of one-man stone dungeons—fifteen to the left, fifteen to the right. These are the calabozos, where they put difficult prisoners. Each cell has one window, perched twelve feet above the ground—too high for prisoners to see anything, its only purpose to vent the room. Inside each occupied cell is a single item: a bucket, covered with either a shirt or a towel to help contain the odor. Emanating from each bucket is a dotted line that moves along the floor and toward the iron door. They aren’t lines exactly. They’re slow moving caravans of cockroach-sized beetles going in and out of the buckets, foraging for food, laying eggs, and rolling dung sausages.

Making his way down the row of cells, he passes by number 5 and sees a rail-thin man, naked from the waist down, half squatting, tilted forward with his shoulder pressed against the wall. His head’s flared to the right, looking back and down. The man’s left hand is spreading his buttocks apart while the fingers of his right hand go up into his rectum, trying to reach the hookworm that’s been causing his itch for the last month—all while he pushes out a bowel movement.

Santiago now stands in front of the open iron door of calabozo number seven, his smile still hanging across his face. A plume of cigarette smoke hits the back of his head. Then he feels the whack of a baton against his calves, followed by a kick. Without looking backward, he laughs and says a final gracias to his sweaty and exhausted puchungitos. He waits for the clopping of the guards’ footsteps to die down to nothing, then moves to the center of his cell, sits down on the damp floor, and crosses his legs. He closes his eyes, and listens to the waves of San Juan bay from a few hundred feet away. Suddenly, there’s a shriek of joy. The man in calabozo number 5 managed to grab hold of the hookworm he’s been probing for, and pulled a large section of it out of his rectum. A moment later, el contador’s voice chimes in: ‘1492, 1493—’. Santiago feels his heartbeat quicken. His smile sags a bit, but he keeps it. Through that smile, he absorbs this place from a distance—is able to see it for what it is, while standing at an angle to it. The smile allows Santiago to laugh, thinking of how the guards turned their faces when the warden spoke. La Princesa, he thinks to himself, is a remarkable Rube Goldberg inspired expeller that could only exist by accident—a sink trap of the foulest effluents that can be squeezed out of distressed men, each leaking and coagulating at different rates and viscosities. Perhaps three parts sweat, fungus, and saliva; one part moldy bandage; two parts blood, tears, and pus; five parts diarrhea, feces, vomit, and hookworm; a dash of semen and earwax—all braising in tropical humidity, all to produce a single output: an odor—a scaled up version of whatever’s inside the warden’s gut. The essence of this place is not so much the odor itself, as the hideous process that forces men to breath in, chew up, and swallow that odor, all the while squeezing them in its expeller, capturing the runoff, and piping it back into the air where it’s breathed in, chewed up, swallowed, and shat out again by the same men, all living inside the stone anus of San Juan. Santiago waits for el contador to reach one thousand five hundred and eighteen. When he does, he lets go of the smile, and indulges himself in a memory.

1518

In 1518, everyone in Santiago’s village knew him as the quiet handsome boy who climbed trees and watched frogs for hours in silence. Though neither he nor they knew it at the time, they lived in a place that would one day come to be called Aguadilla on the western coast of Puerto Rico. Santiago could mimic the sounds of birds and frogs, and would make everyone in the village laugh with his impersonations—especially Anagui his three year old sister. For her, he would hunch down low and loudly chirp like a coqui frog. He would sometimes climb a palm tree very fast, and once at the top, belch loudly and shimmy all the way down in a chaotic-looking backwards freefall, hands and feet slapping at the trunk of the tree the whole way to the ground.

The Yellow Haired Man

Then one day, a yellow haired man showed up—walking right out of the tree line with a caravan of bearded men, all loudly and clumsily stepping on everything in sight, every one of them stinking like a sulfurous bag of buttholes and armpits. As soon as Santiago saw these men, he recognized that he was looking at something new—something he lacked words to describe. On the day of his arrival to Santiago’s village, the yellow haired man gathered everyone together, and showed them a small round object. He called it a hawk’s bell—a hollow globe of brass with an eyelet on one end, and a single small hole punched into its chassis. Normally, a pea-sized metal clapper of some sort would be dropped into that hole so it could make noise when shaken up. Then a loop of leather would be passed through the eyelet, so the entire thing could be tied to the leg of a hunting bird during sport falconry. The gentlemen of Europe attached these noise makers to the legs of falcons, trained them to hunt with the bell, and bring back what they caught. Simply amazing. The yellow haired man wasn’t a gentleman, and had no interest in birds. He wanted every Taino over the age of 14 to wear a hawk’s bell around their neck, then go out into the rivers and streams looking for gold. He explained, using pantomime and loud words spoken in Spanish and Dutch, that he expected every hawk’s bell to be brimming to the top with shiny gold; and that he’d return in five months to check. And then he withdrew a twenty inch dagger which he called a poignard, and tapped his nose with it, laughing as he ogled the women and children. Then he handed out hawks’s bells to each Taino over the age of 14, and noisily walked back into the tree line, toward a tall ceiba tree. All the people of Santiago’s village were glad that the bearded men were gone, but were happy to have the hawk’s bells, and enjoyed the noise they made.

Santiago had watched these men from a distance, perched from up on top of one of the huge plank buttresses of a ceiba tree. When they marched past him, he locked eyes with the yellow haired man, who signaled his caravan to stop.

“Come down here!” he had said. Santiago didn’t understand the words, but understood the intent perfectly. With an agility that surprised everyone, he bounded down effortlessly, executing a combination of grabbing, leaping, and skidding to arrive on a spot of grass close by the caravan of men, who were laughing and loudly talking amongst themselves. The yellow haired man reached into a leather pouch, and grabbed a hawk’s bell and walked over to Santiago. Up close, the thing was remarkable—unlike anything Santiago had ever seen. He wanted to hold it immediately, but he stood there, frozen in place. The yellow haired man stopped within two feet of Santiago, and examined the boy—judged him to be between 12 and 15 years old. Like all of the other male Tainos, he was dressed only in a loincloth. His arms, legs, and chest were all hairless and very clean. The boy smelled like the forest—like leafy water. The yellow haired man stepped in closer, then placed a leather loop of the hawk’s bell around Santiago’s neck, brushing by so closely, he could smell the remnants of the man’s last meal. Looking around, Santiago saw that many of the bearded men had brown stains on their sleeves. He suspected they didn’t know how to clean themselves. All at once, he wished more than anything not to be there, but was afraid. The yellow haired man stood there for a while without saying a word, stroking his hair and squeezing at his shoulders, occasionally glancing around at the other men. The men of the caravan were beginning to make more noise, maybe as a signal to the yellow haired man. Patting his own chest softly, he looked at Santiago and said one word—“Spillers.” And then they were gone. Santiago ran back to the village, clutching at the hawk’s bell, eager to tell Anagui a new story about how he met a man with yellow hair.

That was 11 July, 1518—roughly five months before the triggering event that permanently altered John Spillers’ elliptical luminsescence. This is annotated in FM-5137, with supplemental notes collected by Dr. Vandyck of Area J.