3. The Memories of Trees & Men

The Grass Cutting Area—We peek into a top secret facility at Ramey Air Force Base, and learn about two of its occupants: a 460 year old ceiba tree and Captain Cristian Monserrate Sepulveda

Previously—In episode 2, Dr. Esteberger of Area J explains point clouds, FOJIP polyhedrons, and type 2 sims, then draws our attention to the fact that John Spillers was one of the 39 men left behind at La Navidad in 1492—that Spillers stopped aging in 1518 as a side effect of the deformation of his human luminescence. He also suggests that Spillers has become unclamped from the human layer of the Event Stream.

“Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so that each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.”

— Area J Operator’s Field Manual 5137 (Tenet #1)

The Grass Cutting Area

When Dr. Esteberger described the GRASS CUTTING AREA of Ramey Air Force Base to his audience, he was of course correct in all the details he included. But there were many interesting things he didn’t mention—chiefly, the hard-to-believe level of biodiversity surrounding the area. Despite being half the size of New Jersey, Puerto Rico is a tightly packed Tetris configuration of jungles, coral reef systems, mangrove swamps, wet alpine forests, dry rocky coastlines, and bioluminescent lagoons, supporting over 3,100 native and alien species of flora.

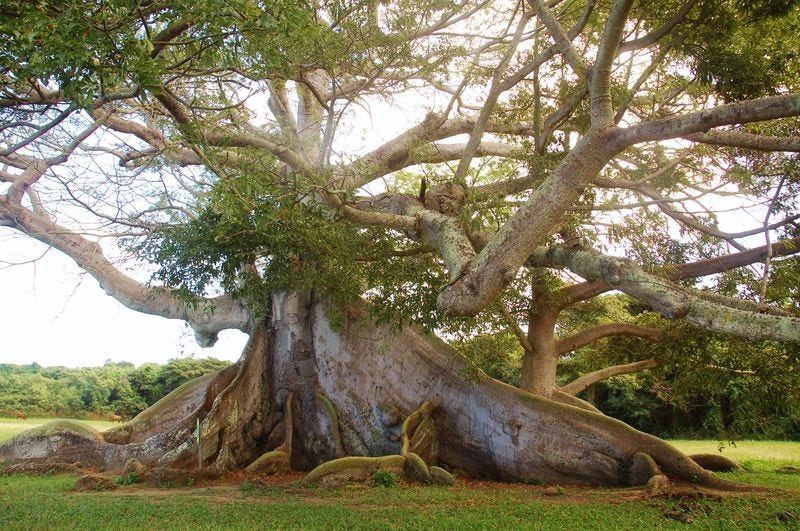

There are 667 species of trees alone. Some, were brought by neotropical migratory birds that long ago, through some incredible twist of weather and dumb luck, rode out the ocean currents and hurricane-force winds from Africa all the way to the Antilles. A few, like the ceiba tree, were brought by Taino traders, who traveled from island to island throughout the Caribbean sea—centuries before the arrival of the Admiral of the Ocean Sea. The Taino were an Arawak people who ventured out from South America, around the year 1200CE, to explore and settle the islands of the Antillean chain. They built hundred-man canoes from the ceiba—a tree they believed to be the daughter of YaYa, the all-powerful goddess. These light grey trees can grow up to 150 feet in height—as high as the statue of Liberty—and are supported at the bottom by triangular shaped woody growths called buttresses, resembling the architectural flourish of the same name—the kind you’d see on the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Because of their thick trunks, lightweight wood, and soaring heights, the ceiba was an ideal canoe-building material, capable of easily withstanding years of hundred mile ocean treks. According to island myth, when the Taino would go looking for a suitable ceiba to cut down, the forest would speak to them, letting them know if it approved or disapproved. If approval was given, the forest would explain how the canoe should be shaped and decorated in order to honor the spirit of the tree.

Inside the GRASS CUTTING AREA, there is a single ceiba tree, conspicuously towering eighty feet above a dense thicket of magnolias. This giant of a tree stood just two feet high in 1492, when the Admiral of the Ocean Sea ran the Santa Maria aground with John Spillers aboard. The tree was three feet tall when the Admiral returned in 1493 and discovered all his men dead or missing—all except John Spillers. By the time Ponce de León arrived in 1508, and began unloading his ships at Guaynabo, just 75 miles to the east, the tree stood 19 feet high. In that year, John Spillers was still human—still aging. By 1511, when the Tainos rebelled against the Spaniards under the Cacique Agüeybaná, the tree stood 21 feet high. Mr. Spillers had not yet discovered his predilection for cutting the noses and lips off of children. That came the very next year in 1512. By 1518, he had figured out the exact methods and procedure for cutting a person’s feet off, cracking open the tibiae right at the ends where the spongy parts are, then slow burning them there at that spot, waiting for the marrow to come bubbling out like coagulated tar. It was December of that year that he managed to keep a man alive for twelve hours during the ordeal. This is the year he stopped being human; stopped aging—when his elliptical luminescence changed, and started developing a debris trail. This is annotated in FM-5137, with supplemental notes collected by Dr. Vandyck of Area J. By the year 1619, the tree stood eighty feet high—its rate of growth significantly slowed to just a few inches per year. It was in July of that year, that John Spillers walked up to the tree, leaned his head against one of its tall plank buttresses, and fell asleep in a patch of shade. At the same time, just 150 miles to the south, an English privateer ship by the name of White Lion sailed past—headed to Old Point Comfort in Hampton, Virginia, carrying between 20 and 30 Africans in the cargo hull. Neither the tree nor Mr. Spillers acknowledged the ship, but the tree bore witness—in its flawless wordless tree-like way—to this, and many other abominable depredations.

On 26 June 1950, when news of the Communist invasion of South Korea reached Puerto Rico, the tree had reached an age of 460 years and a height of 110 feet. It had survived ten tsunamis, eighty nine hurricanes, and countless tropical storms. Though it didn’t give two shits about cold wars, hot wars, domino theory, or Joseph Stalin, Harry S. Truman did—which meant the US military did. The initial consequences of the invasion went unnoticed by the tree, but immediately felt by the members of Ramey Air Force Base—a near total cessation on personnel transfers, permanent party assignments and discharges, and automatic enlistment extensions for nearly every Airman.

Eighty miles away was FBI station chief John Spillers. Not one to waste a perfectly good crisis, he immediately got on the phone with his contacts in DC to obtain authorization for the construction of a small off-the-books interrogation site—extremely low profile in his words, which they promptly approved. Within a week, the consequences of the North Korean incursion had at last collided with the tree. A section of Air Force electricians arrived one day, sent a few men shimmying up into the crown to install fastener clips for an FM line-of-sight transmission system. Over the next eleven weeks, the tree watched as men, bucket loaders, and five ton trucks came in and out of the area—excavating, pouring, tamping, framing—a perfect sixteen hundred square meter construction site footprint for a future camp. And then one day, there appeared two identical grey concrete buildings on that footprint, each marked with black stenciled lettering—building one and building two. And something new, two hundred meters in front of those buildings—a much smaller square of black concrete, with a single large white letter painted on it—H. Fully enclosing the sixteen hundred square meter camp is nine foot tall wire mesh fencing. Beyond that, a semi-landscaped natural enclosure of 30-foot high magnolia trees mixed in with patches of sugar cane. And a little further out, one very conspicuous hundred and ten foot tall ceiba tree with an FM transmitter fixed to its trunk.

Out-of-sight, unmarked, nameless, and completely invisible from the closest two-lane thoroughfare, Spillers’ interrogation site is operated like a compound within a compound—staffed by a twelve man Army detachment taken from members of the 65th infantry regiment out of Camp Las Casas in Santurce. There’s a single point of entry—always manned by a team of two, with two more teams of two providing overwatch from bunkered machine gun nests a hundred meters in.

Building one contains the in-processing room, detainee quarters, interrogation rooms, and offices. This is where the interrogations happen.

Building two contains the barracks, mess hall, gymnasium, and recreation area. When the men originally moved in, everyone was shocked at how nice all of it was—especially the kitchen appliances and showers. They had never before seen dormitory style two-man barracks or shitters enclosed in stalls with actual doors. There was a reason for this: to ensure that the men would keep to themselves; so there’d be minimal to no need for them to use the facilities at Ramey. The commanding officer, Captain Cristian Monserrate Sepulveda, clocked this immediately when he toured the place a week before the move-in date with the Air Force Quartermaster—a bookish man by the name of Barnes. He could tell from Barnes’ bothered fidgeting and tortured eyeball rolling, what was going on in his head: these facilities are too nice—for a bunch of Puerto Ricans. When Barnes finally handed over the keys, Sepulveda passed him a weapons and ordnance list, and said, “I’m sure Mr. Spillers will OK all of this.” Barnes’ face went red and he left without saying a word, stomping the gravel the entire way to his jeep. All the items on that list were delivered the next day.

Having come from an Army infantry background, and therefore already giving zero shits about what the Air Force thinks, Sepulveda’s list reflected the operational requirements of a twenty man infantry detachment—one standard-issue M-4 (with bayonet) per man, two M-240 machine guns, four 38 Colt Commando revolvers, forty M16 anti-personnel mines, ten crates of hand grenades, four Bangalore torpedoes, two hundred pounds of TNT, a crate of non-electric blasting caps, four spools of det cord, and AMPLE ammunition.

One of the captain’s first orders of business after moving in was to harden the security of the camp. He ordered the installation of concertina on top of the fence, built the machine gun nests, and emplaced mines in the clearing between the fence and the magnolias. He also had some of the senior NCO’s improvise directional mines in front of and behind the entry point. By October, everything was in place. That first monday morning formation, he congratulated the men on a job well done, and in a booming voice, proclaimed the words he used to say at Camp Las Casas… “This is my house!”

A few months prior to taking command of the detachment, Sepulveda held the rank of major. He was the 65th regiment’s battalion XO—on his way to getting his lieutenant colonel’s silver oak leaves. But then, PORTREX happened—a two week long amphibious assault simulation involving the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines—staged on the island of Vieques. Toward the end, with ten thousand sailors and Marines about to set sail back to Norfolk Virginia, all wanting just one last big night out, Sepulveda found himself in el Bosque bar in the small barrio of Puerto Ferro, nursing a can of Medalla beer. Outside, the town was crawling with white, green, tan, and blue uniforms—men pissing in the streets, chanting, singing, kicking over garbage cans. Nearby families locked their doors and turned off all the lights.

Stapled to the court martial’s supporting documents, there’s a handwritten letter, provided by a barrio resident who claims to have seen everything. That letter is accompanied by a typed translation. It was read aloud by a Navy JAG lawyer who spoke in crisp Saint Louis English. “According to a translation of the civilian witness’ statement,”…

“Two Marines and a Navy corpsman were standing outside the front door of Julian Felipe Francis’ home making a lot of noise. We all call him Mapepe. He’s the owner of El Bosque bar, and father to twenty year old Carmen Francis. The Marines followed Mr. Francis home after he closed his bar, and began shouting, singing, and urinating on the side of his house—demanding to have a date with his daughter. Major Sepulveda must have heard the noise because he showed up very fast and ordered the men to go back to their ship. The men were all drunk, and began yelling at Major Sepulveda. One of them called him shine. I don’t know what that means.”

When the JAG lawyer read that part aloud, he snickered at the word shine, and exchanged a glance with the presiding Admiral. Looking back at the letter, he continued reading.

“The other two just used the word nigger… over and over. Things were getting very crazy. Then Mapepe came out of his door with a shovel. He started saying something, but one of the Marines grabbed the shovel out of his hands, threw it to the ground, and punched Mapepe in the mouth very hard. Mapepe is old, he would have turned 70 this Christmas eve. I think he fell backwards and hit his head. He was knocked out, and in very bad shape. Maybe that’s why he died at the hospital later. Major Sepulveda went at the men right away. He kicked the Marine first—the one with the shovel—kicked him right in the stomach, very hard. Then he beat up the other two men with his hands. It was over very quickly. The first Marine—the one who hit Mapepe—he ran away. When he came back, there were many military police who arrested Major Sepulveda.”

Major Sepulveda’s court martial was unusual in two respects. First, no witness testimony was sought or even permitted from the other 65th regiment troops present in the bar that night—fellow Puerto Rican soldiers in Sepulveda’s chain of command. Second, the court martial’s final disposition was determined by a Navy admiral, with no input from the Army. Major Sepulveda was reduced in grade to Captain, docked one month’s pay, confined to quarters for one month, and an official disciplinary reprimand was filed in his DD-214.

When the 65th regiment returned to Camp Las Casas, news of the court martial spread quickly throughout the battalion. Then 26 June and the North Korean incursion came around. Captain Sepulveda was ordered to lead a twenty man detachment in the middle of a nameless patch of grass inside of Ramey Air Force Base on the other end of Puerto Rico. When this happened, two hundred hands went up to volunteer.

Damn hat was good!